How do we take responsibility for a technology that is used almost everywhere? As we develop more and more uses of artificial intelligence (AI), the challenges grow to get an overview of how this technology can affect people and human rights.

Although AI legislation is already being developed in several areas, Rowena Rodrigues argues that we need a panoramic overview of the widespread challenges. What does the situation look like? Where can human rights be threatened? How are the threats handled? Where do we need to make greater efforts? In an article in the Journal of Responsible Technology, she suggests such an overview, which is then discussed on the basis of the concept of vulnerability.

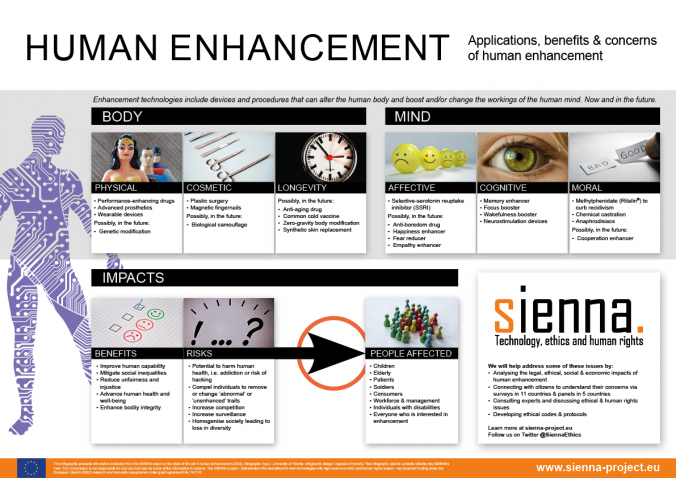

The article identifies ten problem areas. One problem is that AI makes decisions based on algorithms where the decision process is not completely transparent. Why did I not get the job, the loan or the benefit? Hard to know when computer programs deliver the decisions as if they were oracles! Other problems concern security and liability, for example when automatic decision-making is used in cars, medical diagnosis, weapons or when governments monitor citizens. Other problem areas may involve risks of discrimination or invasion of privacy when AI collects and uses large amounts of data to make decisions that affect individuals and groups. In the article you can read about more problem areas.

For each of the ten challenges, Rowena Rodrigues identifies solutions that are currently in place, as well as the challenges that remain to be addressed. Human rights are then discussed. Rowena Rodrigues argues that international human rights treaties, although they do not mention AI, are relevant to most of the issues she has identified. She emphasises the importance of safeguarding human rights from a vulnerability perspective. Through such a perspective, we see more clearly where and how AI can challenge human rights. We see more clearly how we can reduce negative effects, develop resilience in vulnerable communities, and tackle the root causes of the various forms of vulnerability.

Rowena Rodrigues is linked to the SIENNA project, which ends this month. Read her article on the challenges of a technology that is used almost everywhere: Legal and human rights issues of AI: Gaps, challenges and vulnerabilities.

Written by…

Pär Segerdahl, Associate Professor at the Centre for Research Ethics & Bioethics and editor of the Ethics Blog.

Rowena Rodrigues. 2020. Legal and human rights issues of AI: Gaps, challenges and vulnerabilities. Journal of Responsible Technology 4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrt.2020.100005

We recommend readings