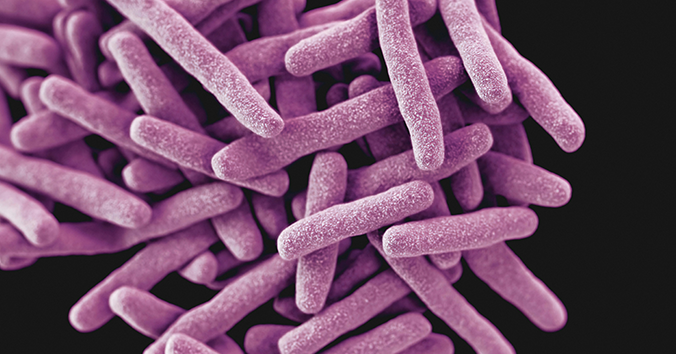

According to the WHO, antibiotic resistance is one of the biggest threats to global health, food security and development. Most of the disease burden is in the global south, but drug resistant infections can affect anyone, in any part of the world. Bacteria are always evolving, and antibiotic resistance is a natural process that develops through mutations. We can slow down the process by using antibiotics responsibly, but to save lives, we urgently need new antibiotics to fight the resistant bacteria that already today threaten our health.

There is a dilemma here: development of new antibiotics is a high-risk business, with very low return of investment, and big pharma is leaving the antibiotics field for precisely this reason. Responsible use of antibiotics means saving new drugs for the most severe cases. There are several initiatives filling the gap this creates. One example is the Innovative Medicines Initiative AMR Accelerator programme, with 9 projects working together to fill the pipeline with new antibiotics, and developing tools and infrastructures that can support antibiotics development.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) to antibiotics and other anti-infectives is a community problem. Managing it requires a community coming together to find solutions and work together to develop research infrastructures. For example, assessing the effectiveness of new antibiotics requires standardised high-quality infection models that can become available to projects, companies and research groups that are developing new antibacterial treatments. Recently, the AMR Accelerator COMBINE project announced a collaboration with some of the big players in the field: CARB-X, CAIRD, iiCON and Pharmacology Discovery Services. This kind of collaboration allows key actors to come together and share both expertise and data. The COMBINE project is developing a standardised protocol for an in vivo pneumonia model. It will become available to the scientific community, along with a bank of reference strains of Gram-negative bacteria that are clinically relevant, complete with a framework to bridge the gap between preclinical data and clinical outcomes based on mathematical modelling approaches.

The benefit of a standardised model is to support harmonisation. Ideally, data on how effective new antibiotic candidates are should be the same, regardless of the lab that performed the experiments. The point of the collaboration is to improve quality of the COMBINE pneumonia model. But who are they and what will they do? CARB-X (Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria Biopharmaceutical Accelerator) is a global non-profit partnership that supports early-stage antibacterial research and development. They will help validation of the pneumonia model. CAIRD (Center for Anti-Infective Research and Development) is working to advance anti-infective pharmacology. They are providing a benchmark by back-translation of clinical data. iiCON has a mission to accelerate and support the discovery and development of innovative new anti-infectives, diagnostics, and preventative products. They are supporting the mathematical modelling to ensure optimal dose selection. And finally, Pharmacology Discovery Services, a contract research organisation (CRO) working with preclinical antibacterial development, will supply efficacy data.

At the centre of this is the COMBINE project, which has a coordinating role in the AMR Accelerator: a cluster of public-private partnership projects funded by the Innovative Medicines Initiative (IMI). The AMR Accelerator brings together academia, pharma industry, patient organisations, non-profits and small and medium sized companies. The aim is to develop a robust pipeline of antibiotics and standardised tools that can be used by others in this community, to help in the fight against antimicrobial resistance.

In parallel, the effort to slow down antibiotic resistance continues. For example, Uppsala University coordinates the COMBINE project, and in 2016, the University founded the Uppsala Antibiotic Center, a multidisciplinary centre for research, education, innovation and awareness. The centre runs the AMR Studio podcast, showcasing some of the multidisciplinary research on antimicrobial resistance around the world. The University is also coordinating the ENABLE-2 antibacterial drug discovery platform funded by the Swedish Research Council, with an open call to support programmes in the early stages of discovery and development of new antibiotics.

Our own efforts at the Centre for Research Ethics & Bioethics are more focused on how we as individuals can help slow down the development of antibiotic resistance, and how we can assess the impact of how you frame antibiotic treatments when you ask patients about their preferences.

Written by…

Josepine Fernow, science communications project manager and coordinator at the Centre for Research Ethics & Bioethics, develops communications strategy for European research projects

Do you want to know more?

EurekAlert! News release: Collaboration to improve the quality of in vivo antibiotics testing, 14 November 2023 https://www.eurekalert.org/news-releases/1007971.

Ancillotti M, Nihlén Fahlquist J, Eriksson S, Individual moral responsibility for antibiotic resistance, Bioethics, 2022;36(1):3-9. https://doi.org/10.1111/bioe.12958

Smith IP, Ancillotti M, de Bekker-Grob EW, Veldwijk J. Does It Matter How You Ask? Assessing the Impact of Failure or Effectiveness Framing on Preferences for Antibiotic Treatments in a Discrete Choice Experiment. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2022;16:2921-2936. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S365624

A shorter version of this post in Swedish

Approaching future issues

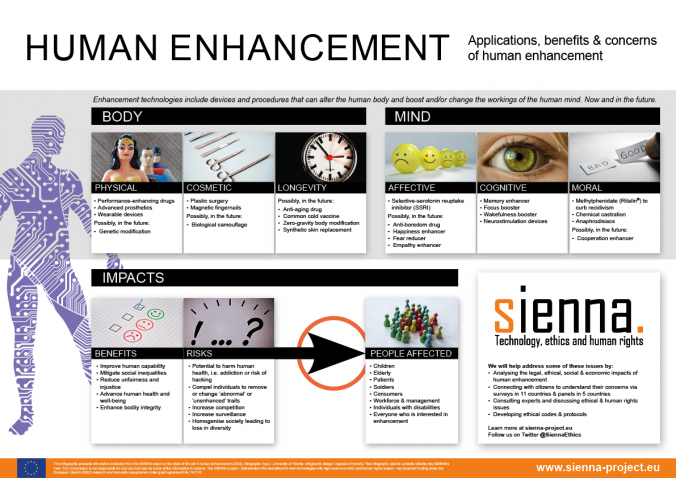

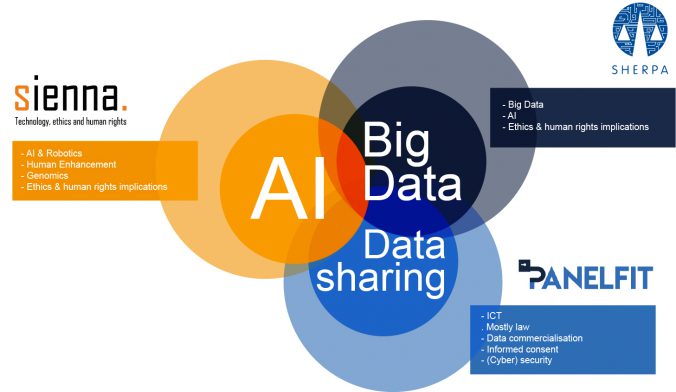

Do you use Google Maps to navigate in a new city? Ask Siri, Alexa or OK Google to play your favourite song? To help you find something on Amazon? To read a text message from a friend while you are driving your car? Perhaps your car is fitted with a semi-autonomous adaptive cruise control system… If any software or machine is going to perform in any autonomous way, it needs to collect data. About you, where you are going, what songs you like, your shopping habits, who your friends are and what you talk about. This begs the question: are we willing to give up part of our privacy and personal liberty to enjoy the benefits technology offers.

Do you use Google Maps to navigate in a new city? Ask Siri, Alexa or OK Google to play your favourite song? To help you find something on Amazon? To read a text message from a friend while you are driving your car? Perhaps your car is fitted with a semi-autonomous adaptive cruise control system… If any software or machine is going to perform in any autonomous way, it needs to collect data. About you, where you are going, what songs you like, your shopping habits, who your friends are and what you talk about. This begs the question: are we willing to give up part of our privacy and personal liberty to enjoy the benefits technology offers.

It is difficult to predict the consequences of developing and using new technologies. We interact with smart devices and intelligent software on an almost daily basis. Some of us use prosthetics and implants to go about our business and most of us will likely live to see self-driving cars. In the meantime, Swedish research shows that

It is difficult to predict the consequences of developing and using new technologies. We interact with smart devices and intelligent software on an almost daily basis. Some of us use prosthetics and implants to go about our business and most of us will likely live to see self-driving cars. In the meantime, Swedish research shows that

Recent Comments