Why is the question of truth so marvelous? A common attitude is that the question can make us check that our opinions really are correct before we express them. By being as well-informed as possible, by examining our opinions so that they form as large and coherent a system as possible of well-considered opinions, we can in good conscience do what we all have a tendency to do: give vent to our opinions.

Letting the question of truth raise the demands on how we form our opinions is, of course, important. But the stricter requirements also risk reinforcing our stance towards the opinions that we believe meet the requirements. We are no longer just right, so to speak, but right in the right way, according to the most rigorous requirements. If someone expresses opinions formed without such rigor, we immediately feel compelled to respond to their delusions by expressing our more rigorous views on the matter.

Responding to misconceptions is, of course, important. One risk, however, is that those who are often declared insufficiently rigorous soon learn how to present a rigorous facade. Or even ignore the more demanding requirements because they are right anyway, and therefore also have the right to ignore those who are wrong anyway!

Our noble attitude to the question of truth may not always end marvelously, but may lead to a harsher climate of opinion. So how can the question of truth be marvelous?

Most of us have a tendency to think that our views of the world are motivated by everything disturbing that happens in it. We may even think that it is our goodness that makes us have the opinions, that it is our sense of justice that makes us express them. These tendencies reinforce our opinions, tighten them like the springs of a mechanism. Just as we have a knee-jerk reflex that makes our leg kick, we seem to have a knowledge reflex that makes us run our mouths, if I may express myself drastically. As soon as an opinion has taken shape, we think we know it is so. We live in our heads and the world seems to be inundated by everything we think about it.

“Is this really true?” Suppose we asked that question a little more often, just when we feel compelled to express our opinion about the state of the world. What would happen? We would probably pause for a moment … and might unexpectedly realize that the only thing that makes us feel compelled to express the opinion is the opinion itself. If someone questions our opinion, we immediately feel the compulsion to express more opinions, which in our view prove the first opinion.

“Is this really true?” For a brief moment, the question of truth can take our breath away. The compulsion to express our opinions about the state of the world is released and we can ask ourselves: Why do I constantly feel the urge to express my opinions? The opinions are honest, I really think this way, I don’t just make up opinions. But the thinking of my opinions has a deceptive form, because when I think my opinions, I obviously think that it is so. The opinions take the form of being the reality to which I react. – Or as a Stoic thinker said:

“People are disturbed not by things themselves, but by the views they take of them.” (Epictetus)

“Is this really true?” Being silenced by that question can make a whole cloud of opinions to condense into a drop of clarity. Because when we become silent, we can suddenly see how the knowledge reflex sets not only our mouths in motion, but the whole world. So, who takes truth seriously? Perhaps the one who does not take their opinions seriously.

Written by…

Pär Segerdahl, Associate Professor at the Centre for Research Ethics & Bioethics and editor of the Ethics Blog.

We challenge habits of thought

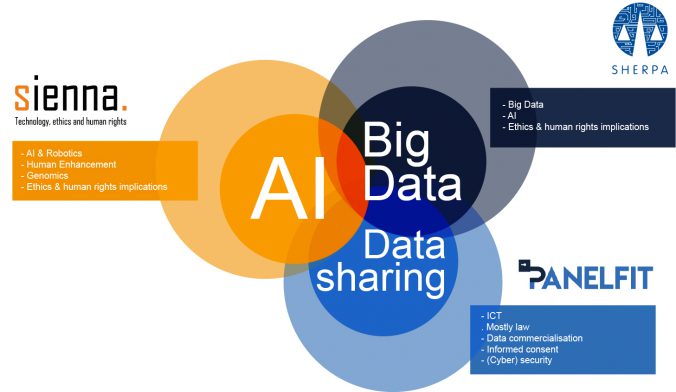

Do you use Google Maps to navigate in a new city? Ask Siri, Alexa or OK Google to play your favourite song? To help you find something on Amazon? To read a text message from a friend while you are driving your car? Perhaps your car is fitted with a semi-autonomous adaptive cruise control system… If any software or machine is going to perform in any autonomous way, it needs to collect data. About you, where you are going, what songs you like, your shopping habits, who your friends are and what you talk about. This begs the question: are we willing to give up part of our privacy and personal liberty to enjoy the benefits technology offers.

Do you use Google Maps to navigate in a new city? Ask Siri, Alexa or OK Google to play your favourite song? To help you find something on Amazon? To read a text message from a friend while you are driving your car? Perhaps your car is fitted with a semi-autonomous adaptive cruise control system… If any software or machine is going to perform in any autonomous way, it needs to collect data. About you, where you are going, what songs you like, your shopping habits, who your friends are and what you talk about. This begs the question: are we willing to give up part of our privacy and personal liberty to enjoy the benefits technology offers.

Recent Comments