I recently read an article about so-called moral robots, which I found clarifying in many ways. The philosopher John-Stewart Gordon points out pitfalls that non-ethicists – robotics researchers and AI programmers – may fall into when they try to construct moral machines. Simply because they lack ethical expertise.

The first pitfall is the rookie mistakes. One might naively identify ethics with certain famous bioethical principles, as if ethics could not be anything but so-called “principlism.” Or, it is believed that computer systems, through automated analysis of individual cases, can “learn” ethical principles and “become moral,” as if morality could be discovered experientially or empirically.

The second challenge has to do with the fact that the ethics experts themselves disagree about the “right” moral theory. There are several competing ethical theories (utilitarianism, deontology, virtue ethics and more). What moral template should programmers use when getting computers to solve moral problems and dilemmas that arise in different activities? (Consider self-driving cars in difficult traffic situations.)

The first pitfall can be addressed with more knowledge of ethics. How do we handle the second challenge? Should we allow programmers to choose moral theory as it suits them? Should we allow both utilitarian and deontological robot cars on our streets?

John-Stewart Gordon’s suggestion is that so-called machine ethics should focus on the similarities between different moral theories regarding what one should not do. Robots should be provided with a binding list of things that must be avoided as immoral. With this restriction, the robots then have leeway to use and balance the plurality of moral theories to solve moral problems in a variety of ways.

In conclusion, researchers and engineers in robotics and AI should consult the ethics experts so that they can avoid the rookie mistakes and understand the methodological problems that arise when not even the experts in the field can agree about the right moral theory.

All this seems both wise and clarifying in many ways. At the same time, I feel genuinely confused about the very idea of ”moral machines” (although the article is not intended to discuss the idea, but focuses on ethical challenges for engineers). What does the idea mean? Not that I doubt that we can design artificial intelligence according to ethical requirements. We may not want robot cars to avoid collisions in city traffic by turning onto sidewalks where many people walk. In that sense, there may be ethical software, much like there are ethical funds. We could talk about moral and immoral robot cars as straightforwardly as we talk about ethical and unethical funds.

Still, as I mentioned, I feel uncertain. Why? I started by writing about “so-called” moral robots. I did so because I am not comfortable talking about moral machines, although I am open to suggestions about what it could mean. I think that what confuses me is that moral machines are largely mentioned without qualifying expressions, as if everyone ought to know what it should mean. Ethical experts disagree on the “right” moral theory. However, they seem to agree that moral theory determines what a moral decision is; much like grammar determines what a grammatical sentence is. With that faith in moral theory, one need not contemplate what a moral machine might be. It is simply a machine that makes decisions according to accepted moral theory. However, do machines make decisions in the same sense as humans do?

Maybe it is about emphasis. We talk about ethical funds without feeling dizzy because a stock fund is said to be ethical (“Can they be humorous too?”). There is no mythological emphasis in the talk of ethical funds. In the same way, we can talk about ethical robot cars without feeling dizzy as if we faced something supernatural. However, in the philosophical discussion of machine ethics, moral machines are sometimes mentioned in a mythological way, it seems to me. As if a centaur, a machine-human, will soon see the light of day. At the same time, we are not supposed to feel dizzy concerning these brave new centaurs, since the experts can spell out exactly what they are talking about. Having all the accepted templates in their hands, they do not need any qualifying expressions!

I suspect that also ethical expertise can be a philosophical pitfall when we intellectually approach so-called moral machines. The expert attitude can silence the confusing questions that we all need time to contemplate when honest doubts rebel against the claim to know.

Written by…

Pär Segerdahl, Associate Professor at the Centre for Research Ethics & Bioethics and editor of the Ethics Blog.

Gordon, J. Building Moral Robots: Ethical Pitfalls and Challenges. Sci Eng Ethics 26, 141–157 (2020).

We recommend readings

Do you use Google Maps to navigate in a new city? Ask Siri, Alexa or OK Google to play your favourite song? To help you find something on Amazon? To read a text message from a friend while you are driving your car? Perhaps your car is fitted with a semi-autonomous adaptive cruise control system… If any software or machine is going to perform in any autonomous way, it needs to collect data. About you, where you are going, what songs you like, your shopping habits, who your friends are and what you talk about. This begs the question: are we willing to give up part of our privacy and personal liberty to enjoy the benefits technology offers.

Do you use Google Maps to navigate in a new city? Ask Siri, Alexa or OK Google to play your favourite song? To help you find something on Amazon? To read a text message from a friend while you are driving your car? Perhaps your car is fitted with a semi-autonomous adaptive cruise control system… If any software or machine is going to perform in any autonomous way, it needs to collect data. About you, where you are going, what songs you like, your shopping habits, who your friends are and what you talk about. This begs the question: are we willing to give up part of our privacy and personal liberty to enjoy the benefits technology offers.

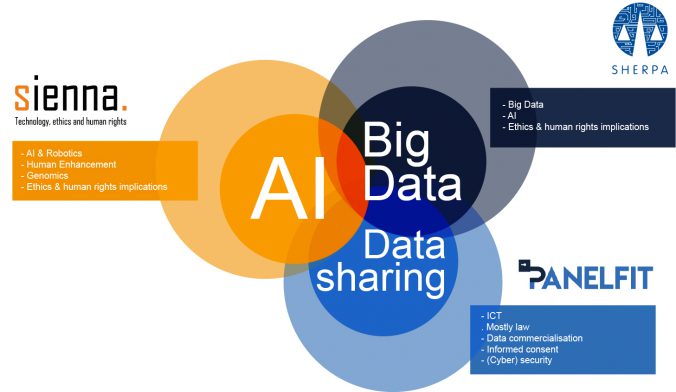

It is difficult to predict the consequences of developing and using new technologies. We interact with smart devices and intelligent software on an almost daily basis. Some of us use prosthetics and implants to go about our business and most of us will likely live to see self-driving cars. In the meantime, Swedish research shows that

It is difficult to predict the consequences of developing and using new technologies. We interact with smart devices and intelligent software on an almost daily basis. Some of us use prosthetics and implants to go about our business and most of us will likely live to see self-driving cars. In the meantime, Swedish research shows that