Can artificial consciousness be engineered, is the endeavor even conceivable? In a number of previous posts, I have explored the possibility of developing AI consciousness from different perspectives, including ethical analysis, a comparative analysis of artificial and biological consciousness, and a reflection about the fundamental motivation behind the development of AI consciousness.

Together with Kathinka Evers from CRB, and with other colleagues from the CAVAA project, I recently published a new paper which aims to clarify the first preparatory steps that would need to be taken on the path to AI consciousness: Preliminaries to artificial consciousness: A multidimensional heuristic approach. These first requirements are above all logical and conceptual. We must understand and clarify the concepts that motivate the endeavor. In fact, the growing discussion about AI consciousness often lacks consistency and clarity, which risks creating confusion about what is logically possible, conceptually plausible, and technically feasible.

As a possible remedy to these risks, we propose an examination of the different meanings attributed to the term “consciousness,” as the concept has many meanings and is potentially ambiguous. For instance, we propose a basic distinction between the cognitive and the experiential dimensions of consciousness: awareness can be understood as the ability to process information, store it in memory, and possibly retrieve it if relevant to the execution of specific tasks, while phenomenal consciousness can be understood as subjective experience (“what it is like to be” in a particular state, such as being in pain).

This distinction between cognitive and experiential dimensions is just one illustration of how the multidimensional nature of consciousness is clarified in our model, and how the model can support a more balanced and realistic discussion of the replication of consciousness in AI systems. In our multidisciplinary article, we try to elaborate a model that serves both as a theoretical tool for clarifying key concepts and as an empirical guide for developing testable hypotheses. Developing concepts and models that can be tested empirically is crucial for bridging philosophy and science, eventually making philosophy more informed by empirical data and improving the conceptual architecture of science.

In the article we also illustrate how our multidimensional model of consciousness can be tested empirically. We focus on awareness as a case study. As we see it, awareness has two fundamental capacities: the capacity to select relevant information from the environment, and the capacity to intentionally use this information to achieve specific goals. Basically, in order to be considered aware, the information processing should be more sophisticated than a simple input-output processing. For example, the processing needs to evaluate the relevance of information on the basis of subjective priors, such as needs and expectations. Furthermore, in order to be considered aware, information processing should be combined with a capacity to model or virtualize the world, in order to predict more distant future states. To truly be markers of awareness, these capacities for modelling and virtualization should be combined with an ability to intentionally use them for goal-directed behavior.

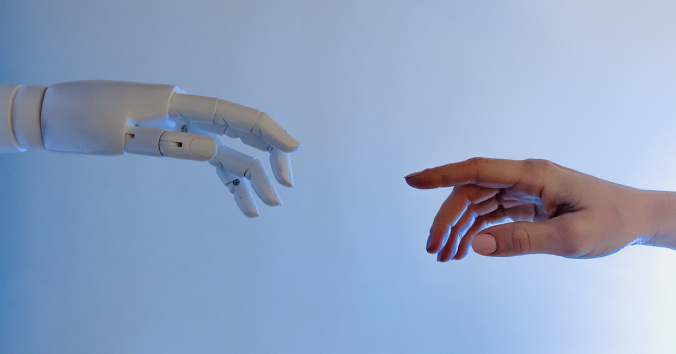

There are already some technical applications that exhibit capacities like these. For instance, researchers from the CAVAA project have developed a robot system which is able to adapt and correct its functioning and to learn “on the fly.” These capacities make the system able to dynamically and autonomously adapt its behavior to external circumstances to achieve its goals. This illustrates how awareness as a dimension of consciousness can already be engineered and reproduced.

Is this sufficient to conclude that AI consciousness is a fact? Yes and no. The full spectrum of consciousness has not yet been engineered and perhaps its complete reproduction is not conceivable or feasible. In fact, the phenomenal dimension of consciousness appears as a stumbling block against “full” AI consciousness. Among other things, because subjective experience arises from the capacity of biological subjects to evaluate the world, that is, to assign specific values to it on the basis of subjective needs. These needs are not just cognitive needs, as in the case of awareness, but emotionally charged and with a more comprehensive impact on the subjective state. Nevertheless, we cannot rule out this possibility a priori, and the fundamental question whether there can be a “ghost in the machine” remains open for further investigation.

Written by…

Michele Farisco, Postdoc Researcher at Centre for Research Ethics & Bioethics, working in the EU Flagship Human Brain Project.

K. Evers, M. Farisco, R. Chatila, B.D. Earp, I.T. Freire, F. Hamker, E. Nemeth, P.F.M.J. Verschure, M. Khamassi, Preliminaries to artificial consciousness: A multidimensional heuristic approach, Physics of Life Reviews, Volume 52, 2025, Pages 180-193, ISSN 1571-0645, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plrev.2025.01.002

We like challenging questions

Recent Comments