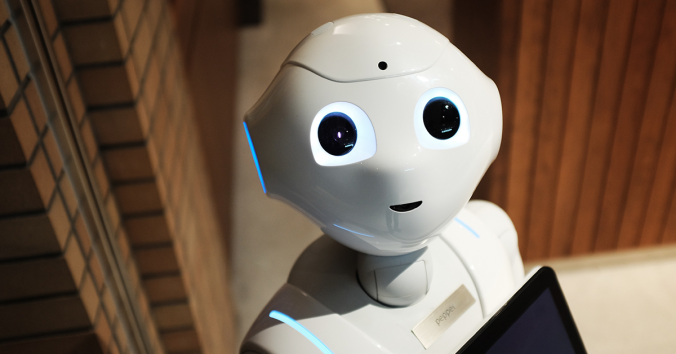

Robots are getting more and more functions in our workplaces. Logistics robots pick up the goods in the warehouse. Military robots disarm the bombs. Caring robots lift patients and surgical robots perform the operations. All this in interaction with human staff, who seem to have got brave new robot colleagues in their workplaces.

Given that some people treat robots as good colleagues and that good colleagues contribute to a good working environment, it becomes reasonable to ask: Can a robot be a good colleague? The question is investigated by Sven Nyholm and Jilles Smids in the journal Science and Engineering Ethics.

The authors approach the question conceptually. First, they propose criteria for what a good colleague is. Then they ask if robots can live up to the requirements. The question of whether a robot can be a good colleague is interesting, because it turns out to be more realistic than we first think. We do not demand as much from a colleague as from a friend or a life partner, the authors argue. Many of our demands on good colleagues have to do with their external behavior in specific situations in the workplace, rather than with how they think, feel and are as human beings in different situations of life. Sometimes, a good colleague is simply someone who gets the job done!

What criteria are mentioned in the article? Here I reproduce, in my own words, the authors’ list, which they do not intend to be exhaustive. A good colleague works well together to achieve goals. A good colleague can chat and help keep work pleasant. A good colleague does not bully but treats others respectfully. A good colleague provides support as needed. A good colleague learns and develops with others. A good colleague is consistently at work and is reliable. A good colleague adapts to how others are doing and shares work-related values. A good colleague may also do some socializing.

The authors argue that many robots already live up to several of these ideas about what a good colleague is, and that the robots in our workplaces will be even better colleagues in the future. The requirements are, as I said, lower than we first think, because they are not so much about the colleague’s inner human life, but more about reliably displayed behaviors in specific work situations. It is not difficult to imagine the criteria transformed into specifications for the robot developers. Much like in a job advertisement, which lists behaviors that the applicant should be able to exhibit.

The manager of a grocery store in this city advertised for staff. The ad contained strange quotation marks, which revealed how the manager demanded the facade of a human being rather than the interior. This is normal: to be a professional is to be able to play a role. The business concept of the grocery store was, “we care.” This idea would be a positive “experience” for customers in the meeting with the staff. A greeting, a nod, a smile, a generally pleasant welcome, would give this “experience” that we “care about people.” Therefore, the manager advertised for someone who, in quotation marks, “likes people.”

If staff can be recruited in this way, why should we not want “cooperative,” “pleasant” and “reliable” robot colleagues in the same spirit? I am convinced that similar requirements already occur as specifications when robots are designed for different functions in our workplaces.

Life is not always deep and heartfelt, as the robotization of working life reflects. The question is what happens when human surfaces become so common that we forget the quotation marks around the mechanically functioning facades. Not everyone is as clear on that point as the “humanitarian” store manager was.

Written by…

Pär Segerdahl, Associate Professor at the Centre for Research Ethics & Bioethics and editor of the Ethics Blog.

Nyholm, S., Smids, J. Can a Robot Be a Good Colleague?. Sci Eng Ethics 26, 2169–2188 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-019-00172-6

Approaching future issues

Recent Comments