During a clinical trial, large amounts of health data are generated that can be useful not only within the current study. If the trial data are made available for sharing, they can be reused within other research projects. Moreover, if the research participants’ individual health data are returned to them, this may benefit the patients in the study.

The opportunities to increase the usefulness of data from clinical trials in these two ways are not being exploited as well as today’s technology allows. The European project FACILITATE will therefore contribute to improved availability of data from clinical trials for other research purposes and strengthen the position of participating patients and their opportunity to gain access to their individual health data.

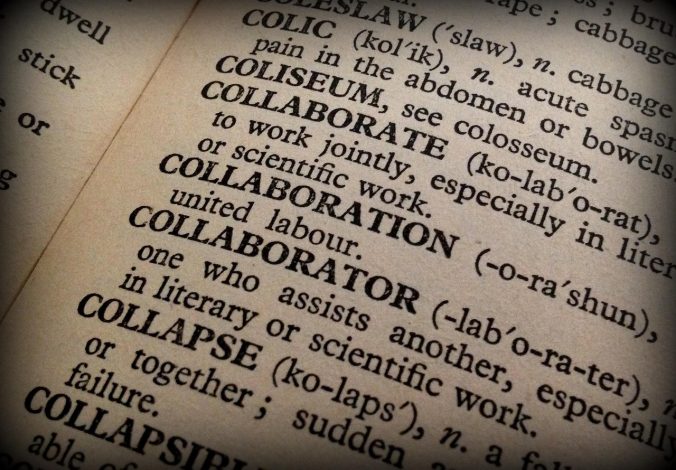

A policy brief article in Frontiers in Medicine presents the project’s work and recommendations regarding the position of patients in clinical studies and the possibility of communicating their health data back to them. The project develops an ethical framework that will put patients more at the center and increase their influence over the studies they participate in. For example, it tries to make it easier for patients to dynamically design and modify their consent, access information about the study and retrieve individual health data.

An extended number of ethical principles are identified within the project as essential for clinical trials. For example, one should not only respect the patients’ autonomy, but also strengthen their opportunities to make informed decisions about their own care on the basis of returned health data. Returned data must be judged to be of some kind of benefit to the individuals and the data must be communicated in such a way that they as effectively as possible strengthen the patients’ ability to make informed decisions about their care.

If you are interested in greater opportunities to use health data from clinical trials, mainly opportunities for the participating patients themselves, read the article here: Ethical framework for FACILITATE: a foundation for the return of clinical trial data to participants.

Written by…

Pär Segerdahl, Associate Professor at the Centre for Research Ethics & Bioethics and editor of the Ethics Blog.

Ciara Staunton, Johanna M. C. Blom and Deborah Mascalzoni on behalf of the IMI FACILITATE Consortium. Ethical framework for FACILITATE: a foundation for the return of clinical trial data to participants. Frontiers in Medicine, 17 July 2024. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2024.1408600

We recommend readings