Sometimes the intellectual claims on science are so big that they risk obscuring the actual research. This seems to happen not least when the claims are associated with some great prestigious question, such as the origin of life or the nature of consciousness. By emphasizing the big question, one often wants to show that modern science is better suited than older human traditions to answer the riddles of life. Better than philosophy, for example.

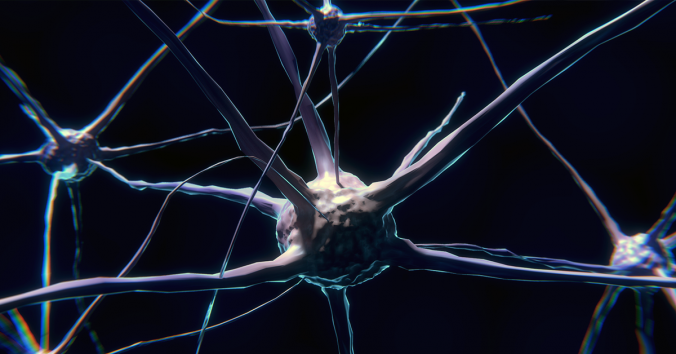

I think of this when I read a short article about such a riddle: “What is consciousness? Scientists are beginning to unravel a mystery that has long vexed philosophers.” The article by Christof Koch gives the impression that it is only a matter of time before science determines not only where in the brain consciousness arises (one already seems have a suspect), but also the specific neural mechanisms that give rise to – everything you have ever experienced. At least if one is to believe one of the fundamental theories about the matter.

Reading about the discoveries behind the identification of where in the brain consciousness arises is as exciting as reading a whodunit. It is obvious that important research is being done here on the effects that loss or stimulation of different parts of the brain can have on people’s experiences, mental abilities and personalities. The description of a new technology and mathematical algorithm for determining whether patients are conscious or not is also exciting and indicates that research is making fascinating progress, which can have important uses in healthcare. But when mathematical symbolism is used to suggest a possible fundamental explanation for everything you have ever experienced, the article becomes as difficult to understand as the most obscure philosophical text from times gone by.

Since even representatives of science sometimes make philosophical claims, namely, when they want to answer prestigious riddles, it is perhaps wiser to be open to philosophy than to compete with it. Philosophy is not just about speculating about big questions. Philosophy is also about humbly clarifying the questions, which otherwise tend to grow beyond all reasonable limits. Such openness to philosophy flourishes in the Human Brain Project, where some of my philosophical colleagues at CRB collaborate with neuroscientists to conceptually clarify questions about consciousness and the brain.

Something I myself wondered about when reading the scientifically exciting but at the same time philosophically ambitious article, is the idea that consciousness is everything we experience: “It is the tune stuck in your head, the sweetness of chocolate mousse, the throbbing pain of a toothache, the fierce love for your child and the bitter knowledge that eventually all feelings will end.” What does it mean to take such an all-encompassing claim seriously? What is not consciousness? If everything we can experience is consciousness, from the taste of chocolate mousse to the sight of the stars in the sky and our human bodies with their various organs, where is the objective reality to which science wants to relate consciousness? Is it in consciousness?

If consciousness is our inevitable vantage point, if everything we experience as real is consciousness, it becomes unclear how we can treat consciousness as an objective phenomenon in the world along with the body and other objects. Of course, I am not talking here about actual scientific research about the brain and consciousness, but about the limitless intellectual claim that scientists sooner or later will discover the neural mechanisms that give rise to everything we can ever experience.

Written by…

Pär Segerdahl, Associate Professor at the Centre for Research Ethics & Bioethics and editor of the Ethics Blog.

Christof Koch, What Is Consciousness? Scientists are beginning to unravel a mystery that has long vexed philosophers, Nature 557, S8-S12 (2018) https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-018-05097-x

We transcend disciplinary borders